'Accordion' gene switch seen

Australian researchers have revealed crucial details on how to switch off genes.

Australian researchers have revealed crucial details on how to switch off genes.

A team at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research (WEHI) has revealed how an ‘accordion effect’ is critical to switching off genes, in a study that could transform the understanding of gene silencing.

It also adds more details to the knowledge of how genes are switched on and off to make the different cell types in the human body as it develops in the womb.

The study could offer a new way to harness gene silencing in the future, to treat or reverse the progression of a broad range of diseases including cancer, congenital and infectious diseases.

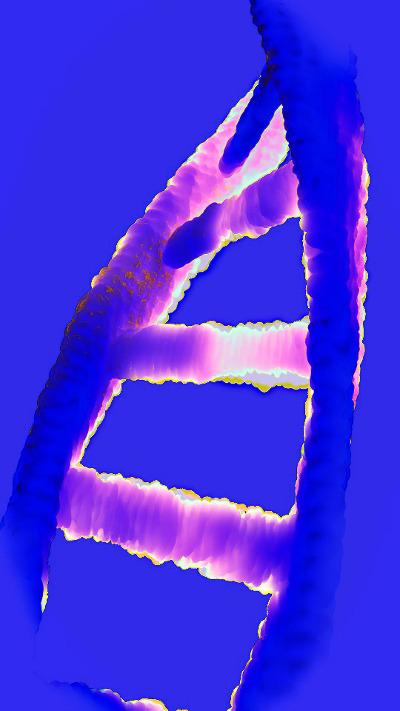

Gene silencing is regulated by how tightly DNA is packed into a cell. The research team led by Dr Andrew Keniry and Professor Marnie Blewitt has revealed a new ‘accordion-like’ trigger that is crucial to the process.

The DNA that makes up human genetic material is wrapped tightly around proteins, like thread wraps around a spool.

When it is loosely packaged, the genes can be switched on, and when it is tightly compacted, genes are switched off.

In the new study, the researchers found that to switch a gene off, the DNA packaging must initially loosen up, before then being tightly compressed.

Professor Marnie Blewitt said discovering the accordion-style trigger took the team by surprise, changing their fundamental understanding to date of this critical process.

“We were amazed to learn that the DNA first needs to relax, to trigger this process,” she said.

“Similar to how an accordion needs to open up before it is compressed to elicit a musical note, we found our DNA needs to be opened up first, before it can be compressed and the gene is silenced.”

Dr Andrew Keniry says gene silencing has amazing therapeutic potential.

“If we could learn exactly how to switch genes off, we may one day be able to switch off detrimental genes in a variety of diseases,” Dr Keniry said.

“If you could switch off the oncogenes that drive cancer, for example, you potentially could have a new treatment.

“To be able to realise this dream, we first need to know how the process happens so it can be mimicked with medicines, and our discovery is one more vital piece of this puzzle.”

The next steps for the research will investigate why the accordion effect is required for gene silencing and the relevance of the process for genes on other chromosomes, such as the autosomes.

Print

Print