Biobank to drive discovery

An Australian-first biobank will be established to improve and discover new treatments for children with genetic muscle diseases.

An Australian-first biobank will be established to improve and discover new treatments for children with genetic muscle diseases.

Experts say that the National Muscle Disease Bio-databank, co-led by Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, Monash University and Alfred Health, will advance research into understanding why children develop genetic muscle diseases.

These diseases, spanning dystrophies and myopathies, are characterised by severe muscle weakness, usually from infancy, that can impact swallowing, breathing and lead to eye problems and learning difficulties.

About 30 people a year are diagnosed with a congenital muscular disease in Australia of which half will have a genetic basis identified.

Murdoch Children’s Dr Peter Houweling says there is an unmet need for affordable treatments that could be fast-tracked into clinical trials.

“Knowledge is limited because Australia lacks a dedicated databank for congenital muscle disorders,” he said.

“Each state undertakes genetic testing via local services but there is no national database that matches clinical information with genetic diagnosis.”

To address this, the biobanking facility housed at Murdoch Children’s will collect patient information and store blood test and skin biopsy samples from children across Australia with genetic muscle disease.

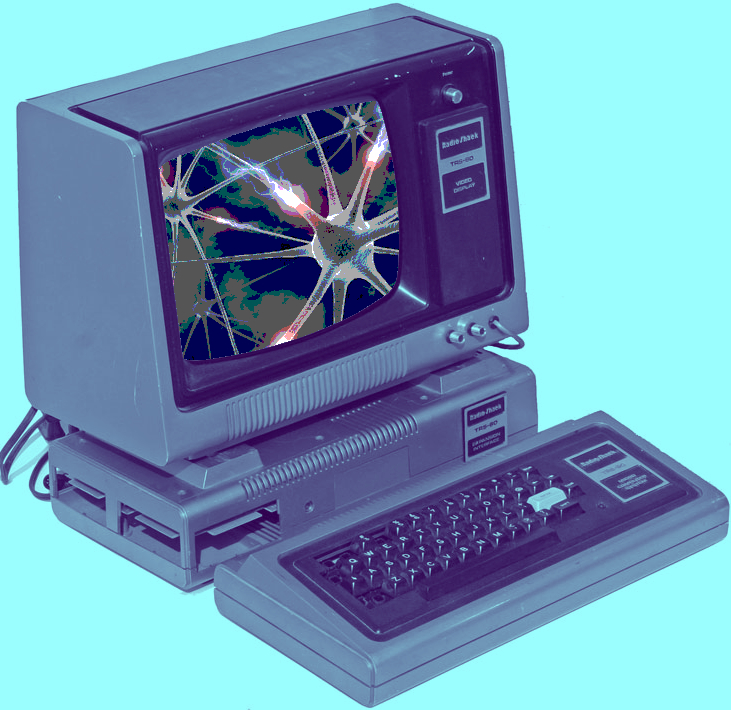

“To understand how muscle is affected by disease, our research team will study the genes, cells and proteins in patient samples using cutting edge technologies,” Dr Houweling said.

“This bio-databank will advance our knowledge of disease mechanisms and has the real potential to discover new and better treatments and fast-track discoveries.”

Monash University’s Professor Peter Currie said genetic muscle disorders have one of the highest disease burdens, greater than that of cancer and multiple sclerosis and greater per case than any other disease.

“The financial cost per year for genetic therapies and loss of productivity for those with muscular dystrophy is $435 million due to a lack of effective treatments,” he said.

For decades, treatments have remained unaffordable for most families and are primarily palliative, aimed at maintaining mobility, respiratory and cardiac functions.

“Congenital muscle diseases are also arguably the most individually impactful with many patients having a poor prognosis, requiring lifelong supportive care including mobility and respiratory support and in severe cases are inevitably fatal,” Dr Currie said.

Alfred Health’s Professor Catriona McLean says that a major hurdle to advancing outcomes was understanding the underlying molecular basis of the diseases, coupled with a need for patient-specific models to develop and test therapies.

“Despite almost two decades of genomic diagnostics in the clinic, patients and families are still left with few answers and ineffective treatment options for disorders that can be fatal in infancy or early childhood,” she said.

“Much of this clinical uncertainty stems from a lack of insight into the disease, which requires innovative thinking and investment into additional programs that can advance beyond genomics.”

Print

Print