Cancer cell switch brings striking results

Excitement is rising around a new cancer treatment that uses a patient’s own cells.

Excitement is rising around a new cancer treatment that uses a patient’s own cells.

Researchers have reported “unprecedented” success with a new type of personalised treatment wherein a patient’s cells are removed and genetically-modified into tumour-killing agents.

Reports say a staggering 94 per cent of patients for whom chemotherapy had not been effective went into remission in one trial.

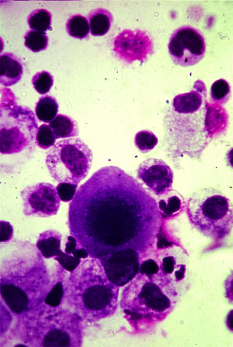

The treatment uses immune system components called T cells.

T-cells spend most of their time hunting for threats throughout the body, but their activity diminishes with some chronic diseases and when rapidly dividing cancer cells turn up as well, the T-cells can be overwhelmed.

With advances in genetic engineering, scientists can now harness and exploit the cells’ natural abilities, so that they specifically target cancer cells.

In this case, researchers at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in the US engineered T-cells to target a molecule called CD19, which is almost exclusively found on a white blood cell called a B-cell.

B-cells confer the ability to seek and destroy tumours originating from these cells, such as certain lymphomas and types of leukaemia.

A patient’s T-cells are removed and modified to include the synthetic receptor before they are reinfused back into the patient.

In tests so far, the modified T-cells appear to offer protection against B-cell cancers.

The most impressive results in limited trials so far came from a group of 35 patients with a white blood cell cancer called acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

In this one group, which 94 per cent of patients went into remission.

In trials with over 40 lymphoma patients, over 50 per cent also saw their cancer symptoms disappear.

But the treatment is not perfect yet.

Some patients experienced severe side-effects, including neurological problems and decreased blood pressure, so the researchers are now focusing on these effects.

Of course it takes several years for any patient to declare themselves ‘cancer-free’, so more long-term follow-up studies are needed.

But as positive results keep pouring in and researchers find more ways to target different cancers, optimism is rising.

Print

Print