Lab lungs laid out

Scientists have developed a step-by-step blueprint to create advanced human lung models in the lab.

Scientists have developed a step-by-step blueprint to create advanced human lung models in the lab.

The new process could accelerate the discovery and development of new drugs and reduce reliance on animal testing.

The new research due to be published in Biomaterials Research is available online as a preprint, led by the University of Sydney’s Dr Huyen Phan with collaborators from Australia, South Korea and China.

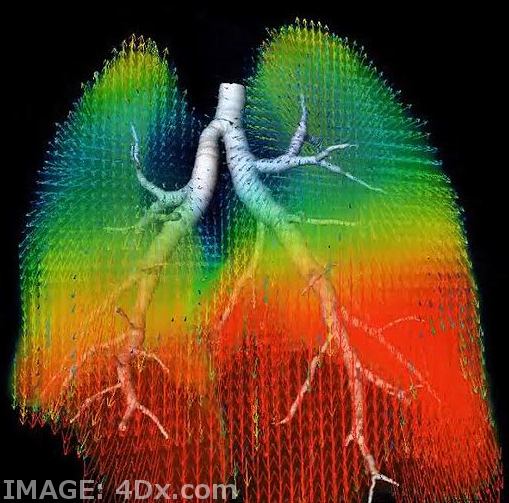

Lab-made lungs, known as organoids or mini organs, are 3D structures grown from human primary cells that mirror real organs in the body. They serve as a testing ground for biomedical research.

Australian researchers report on two different lung models, one of which mimics phase one clinical trials; a healthy lung to study safety of new drugs. The other one mimics phase two trials; a diseased lung that mirrors chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, enabling experts to study the therapeutic effectiveness or superiority of the drugs.

“We take cells directly from patients and then build them in layers as they exist inside the body. So, first you have the epithelial cells, then you have the fibroblasts – we are literally creating a mimic organ that is very much like actual human lungs,” says senior author Professor Wojciech Chrzanowski, Professor of Nanomedicine in the Sydney Pharmacy School, Faculty of Medicine, and member of the Charles Perkins Centre.

Professor Chrzanowski said the models described in the paper, which are more accurate than traditional models, are unique for their ability to emulate the environmental conditions of a human lung. Similar models are now being used by AstraZeneca and the US Food and Drug Administration.

With a traditional cell culture, cells are put into a Petri dish and cultured in static conditions, which is far from what happens in a human body. The new method creates environmental conditions similar to those which exist in the human body, culturing and maintaining models under the micro-environmental conditions of lungs, with air on one side and liquid interface at the bottom, combined with microcirculation.

These two elements combined help emulate the conditions of a human lung, making them more accurate.

Uses for the lung models are not isolated to drug discovery. They can also be personalised to individual patients and be used to test a range of reactions in the lung.

“These mini-lung organoid models can also be used to test toxicity. For example, of silica dust or air pollutants, such as particulates generated during bush fires,” Professor Chrzanowski said.

“Because we can take cells directly from individual patients, we can build a patient’s own model to test the effectiveness of drugs on them.”

Professor Chrzanowski said the lung models could have a major impact on basic science, enabling the discovery of how different organs function and how to design the most effective therapeutic strategies.

The researchers said the huge advantage of their models are their reproducibility, reliability and the ability to conduct research in a cost-effective way at a large scale.

Development of these lung models brings Australia to the forefront of mini organ research, said Professor Chrzanowski, who has been calling for the establishment of a national centre for medical research alternatives to animal methods.

Australia banned cosmetic testing on animals in 2020, and last year the United States passed legislation ending a requirement for new drugs to be tested on animals.

Print

Print