Stem cell embyros tested

Researchers have created embryo-like structures from monkey stem cells.

Researchers have created embryo-like structures from monkey stem cells.

In a groundbreaking study, researchers from the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) in Shanghai have successfully created the embryo-like structures from monkey embryonic stem cells for the first time, and were able to implant these structures into female monkeys, where they elicited a hormonal response similar to pregnancy.

The study, published in the journal Cell Stem Cell, is a significant breakthrough for the field of embryonic development, which is often hampered by ethical issues surrounding the use of human embryos for research.

“Because monkeys are closely related to humans evolutionarily, we hope the study of these models will deepen our understanding of human embryonic development, including shedding light on some of the causes of early miscarriages,” said co-corresponding author Zhen Liu of CAS.

The team started with macaque embryonic stem cells, which they exposed to a number of growth factors in cell culture. These factors induced the stem cells to form embryo-like structures for the first time using non-human primate cells.

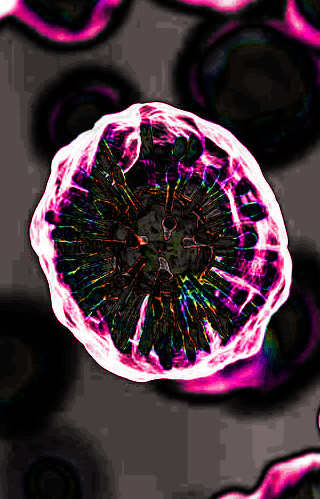

Under a microscope, the embryo-like structures, also called blastoids, were found to have similar morphology to natural blastocysts.

As they further developed in vitro, they formed arrangements that looked like the amnion and yolk sac, and started to form the types of cells that eventually make up the three germ layers of the body.

The blastoids were then transferred into the uteruses of eight female monkeys, where they were found to have implanted in three of them, resulting in the release of progesterone and chorionic gonadotropin, hormones normally associated with pregnancy.

The blastoids also formed early gestation sacs, fluid-filled structures that develop early in pregnancy to enclose an embryo and amniotic fluid. However, they did not form foetuses and the structures disappeared after about a week.

“This research has created an embryo-like system that can be induced and cultured indefinitely. It provides new tools and perspectives for the subsequent exploration of primate embryos and reproductive medical health,” said co-corresponding author Quian Sun of CAS.

The researchers acknowledge the ethical concerns surrounding this type of research, but emphasise that there are still many differences between these embryo-like structures and natural blastocysts.

Importantly, the embryo-like structures do not have full developmental potential.

They note that for this field to advance it is important to have discussions between the scientific community and the public.

“This will provide us with a useful model for future study,” said co-corresponding author Fan Zhou of Tsinghua University.

“Further application of monkey blastoids can help to dissect the molecular mechanisms of primate embryonic development.”

The study could be an important step towards unlocking the secrets of human embryonic development, and have far-reaching implications for reproductive medicine and early intervention in pregnancy-related conditions.

Print

Print