Ultrasound for Alzheimer's studied

Australian experts have found new evidence that ultrasound can help in the battle against Alzheimer’s disease.

Australian experts have found new evidence that ultrasound can help in the battle against Alzheimer’s disease.

A new study by researchers at QIMR Berghofer is the first to examine the technique on brain cells derived from human patients with Alzheimer’s disease, building on previous research on mice and other animal models.

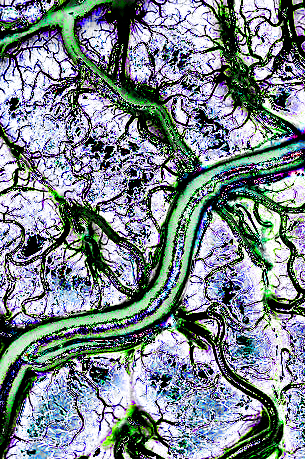

They found that using focused ultrasound coupled with microbubble treatment can create openings in the blood-brain barrier formed by human endothelial cells.

“The blood-brain barrier is a semipermeable barrier that lines blood vessels in the brain and importantly protects brain tissue, but that protective function also prevents the uptake of drugs and therapies targeting brain diseases,” said lead researcher Associate Professor Anthony White.

“We found by using focused ultrasound and microbubble treatment we could weaken the connection between blood-brain barrier cells, which would potentially allow the brain tissue to absorb a drug treatment.

“An abnormal blood-brain barrier has been associated with several neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease, so it’s very important that we better understand how the barrier works and how we can safely penetrate it to combat disease.

“Our study is the first to look at how the blood-brain barrier cells from human patients can be disrupted to improve the uptake of Alzheimer’s therapies, building on previous studies that have explored if ultrasound could be used to reduce amyloid build up in the brains of mice and other animal models.”

The researchers used brain endothelial cells derived from human stem cells of people with a family history of Alzheimer’s disease to understand how those cells of the blood-brain barrier could be weakened.

They injected lipid microbubbles into the cells and then targeted the area with ultrasound which caused the cells to expand and contract, disrupting the connections between the cells, opening the blood-brain barrier. The ultrasound and microbubble treatment technique was developed by researchers at the Queensland Brain Institute.

The ultrasound and microbubble treatment was found to have a longer lasting effect on the brain cells of Alzheimer’s patients than on healthy controls.

“The treatment generated openings in the monolayer of the blood-brain barrier of all patients, but the brain endothelial cells of healthy controls repaired themselves quicker than the Alzheimer’s patient cells,” said researcher Dr Lotta Oikari.

“The blood-brain barrier in Alzheimer’s patients was slower to repair, indicating they would be more receptive to drugs and treatments for longer and that brain ultrasound treatment may have to be adjusted differently depending on the type of disease the patient has.

“It also raises questions whether reduced integrity in the blood-brain barrier, following ultrasound treatment, could lead to lower amyloid levels in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients because the brain tissue could potentially expel the build-up.”

Print

Print